How the neighborhood of Pullman gave birth to Labor Day

Published on July 1, 2022

Pullman looked idyllic, offered a better standard of living than what employees could have afforded elsewhere. But on the inside, none of the advantages of the model city compensated for the restrictions on the freedom of the workmen,

Because of its historical architectural significance, Pullman is ideal for a walking tour. Our Whoa!Guide Colm Ronan has created a 45-minute tour of Pullman that spotlights seven Points of Interest. You can purchase it here.

By 1880, George Pullman had revolutionized passenger railroad travel thanks to his sleeping car when he devised a new plan. His Pullman Palace Car Company purchased 4,000 acres along the Illinois Central Railroad line in Hyde Park Township, several miles south of Chicago, for $800,000. Pullman then set about building a town to house his factory and employees.

Pullman’s impetus was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Then, railroad workers in six states, including Illinois, walked off the job when a long-term economic downturn affected their wages and conditions. Eventually, the National Guard and federal troops were called in to suppress the uprising, and approximately 100 people were killed. Pullman believed that a quaint town away from the temptations of the big city would preclude the need for his workers to revolt.

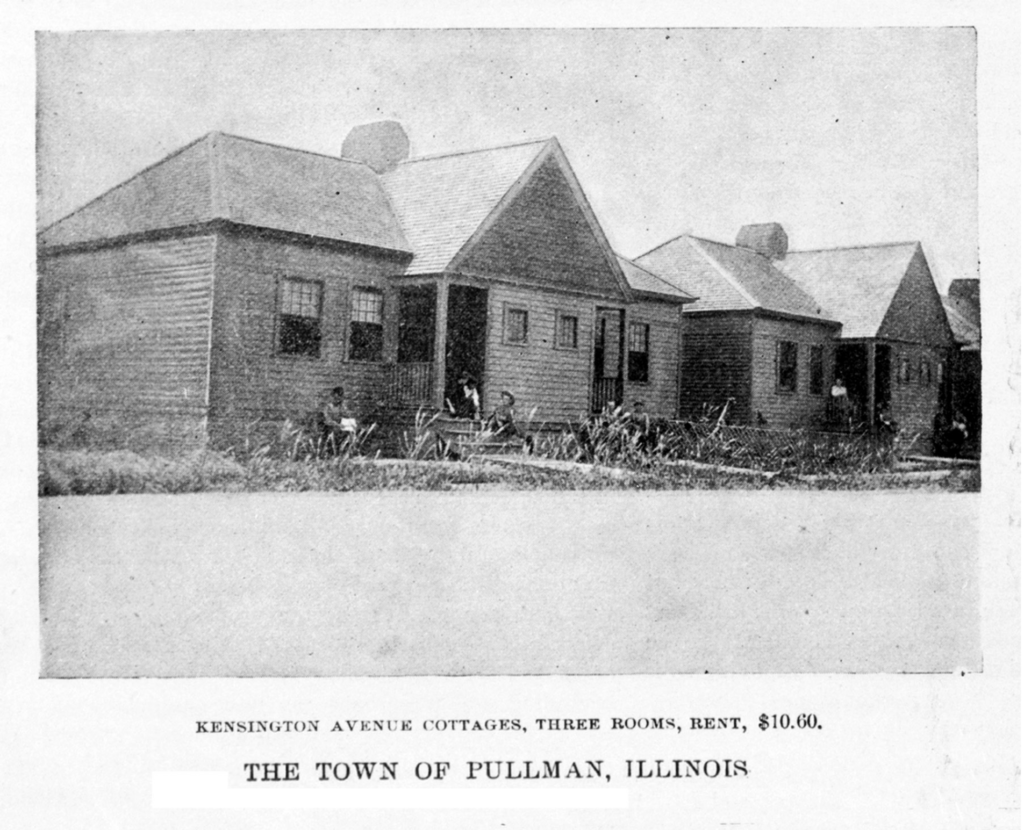

Pullman hired architect Solon Spencer Beman to design the buildings and Nathan Franklin Barrett to lay out the streets and parks. Beman’s brick, Queen Anne-inspired homes ranged from apartments and rowhouses for the workers to mansions for the executives. The town had 30,000 trees, the man-made Lake Vista, a church, hospital, public library, theater, school, the upscale Hotel Florence (named after Pullman’s eldest daughter) and the factory, which had the Administration Building and Clocktower at its core. The town of Pullman welcomed its first resident, a foreman named Lee Benson, on Jan. 1st, 1881.

To most outsiders, Pullman looked idyllic. It was immaculately maintained, with pretty homes that offered a better standard of living than what Pullman’s employees could have afforded elsewhere. Labor commissioners from several states visited Pullman in 1884 and praised how it shielded women and children from the dangers of urban life. An article in an 1883 issue of Agricultural Review called Pullman “the youngest and most perfect city in the world.”

But on the inside, there were issues. Pullman instilled a strict dress code and banned alcohol, with the sole exception being for guests at the hotel. Pullman didn’t allow independent newspapers or town meetings, and his inspectors could enter homes to make sure they met cleanliness standards.

The secrets of Pullman

The Chicago Tribune took notice. “None of the ‘superior,’ or ‘scientific’ advantages of the model city will compensate for the restrictions on the freedom of the workmen, the denial of opportunities of ownership, the heedless and vexatious parade of authority, and the sense of injustice arising from the well-founded belief that the charges of the company for rent, heat, gas, water, etc. are excessive –if not extortionate,” read an article dated September 21st, 1888. “Pullman may appear all glitter and glow, all gladness and glory to the casual visitor, but there is the deep, dark background of discontent which it would be idle to deny.”

Still, a year later, the town of Pullman became part of Chicago when Hyde Park Township was annexed as part of the city’s rapid expansion. However, George Pullman still owned the homes and shops.

The biggest problem came during the Panic of 1893. Pullman’s railroad business suffered, and he laid off some workers while cutting wages and increasing hours for others. Ironically, this was the exact problem Pullman hoped to avoid by building the town. And it was exacerbated by his autocratic rule. Even worse, he refused to lower rents or prices for items in the shops, because that would further affect the return on investment to his stockholders, which had never reached the 6 percent that he originally promised.

The strike

The situation remained unresolved and George Pullman refused to meet with the committee that had been formed to address the issues. On May 11th, 1894, the employees went on strike. Six weeks later, Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the American Railway Union, called for a boycott by union members of all trains that use Pullman cars. The action had a major impact on interstate commerce and mail delivery. At a rally on June 29th, strikers derailed a locomotive on a mail train and set buildings on fire. The federal government got involved with a never-before-used tactic. They got an injunction to stop the strike. When the court order was ignored, President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to Chicago in early July.

A few days before his action, however, Cleveland, a Democrat, needed to show that he was otherwise pro-labor. He signed legislation that designated the first Monday in September to be Labor Day.

The arrival of the military and the Illinois National Guard further escalated the tension and violence. Approximately 30 people were killed on July 7th when troops fired into the mob. Within two weeks, the Pullman Strike was officially over and Debs was arrested for several federal crimes related to the strike.

Although George Pullman emerged victorious in the strike, his reputation was tarnished because of the policies that caused the strike and his subsequent refusal to negotiate. He died on Oct. 19th, 1897. Almost exactly one year later, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the Pullman Palace Car Company had to sell off all of its non-industrial land, although the company was able to defer the divestment until 1907. Residents were given the first option to purchase the homes in which they lived.

In 1925, the company’s labor practices made national news again. Pullman was the nation’s largest employer of Blacks, but the only jobs open to them were as porters on the trains. Porters provided exceptional service while working incredibly long shifts for a sub-standard hourly wage. They made up the difference through tips, but they also had to pay for their meals, lodging, uniform and supplies while on the job.

To fight for better wages and conditions, a group of Pullman porters led by A. Philip Randolph and Milton P. Webster, formed the first Black labor union: the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. After three years of getting nowhere, the BSCP threatened a strike. Fearing such an action would fail, it was called off at the last minute. It wasn’t until 1937 that an agreement was reached that improved their conditions. The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum opened in Pullman to promote Randolph’s legacy and the roles African-Americans played in the labor movement.

A legacy stands

The decline of the Pullman Company after World War II coincided with the neighborhood’s fall into disrepair. By 1960 there was talk of demolishing Pullman in favor of an industrial park, but residents banded together to spare it from the wrecking ball. The company ceased operations in 1969, the same year the neighborhood was declared a National Historic Landmark District. Within a few years Pullman obtained similar status on the state and city levels. In 1991, the State of Illinois purchased the distinctive Hotel Florence and the Administration Building and Clock Tower.

In 2015, President Barack Obama went one step further, declaring the Pullman District to be a national monument. This put the area under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. Pullman is the only national monument in the city of Chicago. In 2020, work began to turn the Administration Building and Clock Tower into a Visitors Center, as it had previously been severely damaged by a fire in 1998.

Obama’s action has helped revitalize Pullman. The neighborhood has recently seen fresh growth with a new food hall, an art space and other businesses opening up.

The Adventure starts when you say it does.

All eATLAS Adventures are designed and built by experienced eATLAS Whoa!Guides. They're always on. Always entertaining. And always ready to go.

Check out our Adventures!