The Story of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871

Published on October 3, 2024

Explore how Chicago rebounded from the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 with eATLAS’ Adventures of historic neighborhoods that were devastated in the disaster. Ronnie Frey’s Art Deco Madness tour visits 12 skyscrapers from the ‘20s and ‘30s, and Mimi Fron’s Near Northside Neighborhoods takes you to 20 historic sites in Gold Coast and Old Town.

By Dave Lifton (@daveeatschicago)

Due to a unique convergence of industry, agriculture, and geography, Chicago’s rapid growth in its early years was unprecedented. By 1870, a mere 33 years after its incorporation, it was already the fifth largest city in the U.S., with just under 300,000 people. To meet the demand, wood, which was plentiful and inexpensive from nearby forests, was used to not only construct bridges and thousands of buildings, but to pave bridges, 57 miles of streets and 561 miles of sidewalks.

The summer of 1871 had been hot and incredibly dry, with only an inch of rain falling in Chicago from July 4th through September. In the first week of October, 20 fires had broken out, exhausting the fire department and depleting its resources. On Sunday, Oct. 8th, following a 17-hour fire the day before, the Chicago Tribune noted that “the absence of rain for three weeks had left everything in so dry and inflammable a condition that a spark might set a fire which would sweep from end to end of the city.”

That night, at about 8:30, a fire broke out inside Patrick and Catherine O’Leary’s barn at 137 DeKoven St. on the Near West Side. A combination of a wrong address and a failed alarm box meant that the fire department didn’t arrive until about 90 minutes later. The lengthy delay allowed the fire to spread, aided by the dried-out wood and strong southwestern winds.

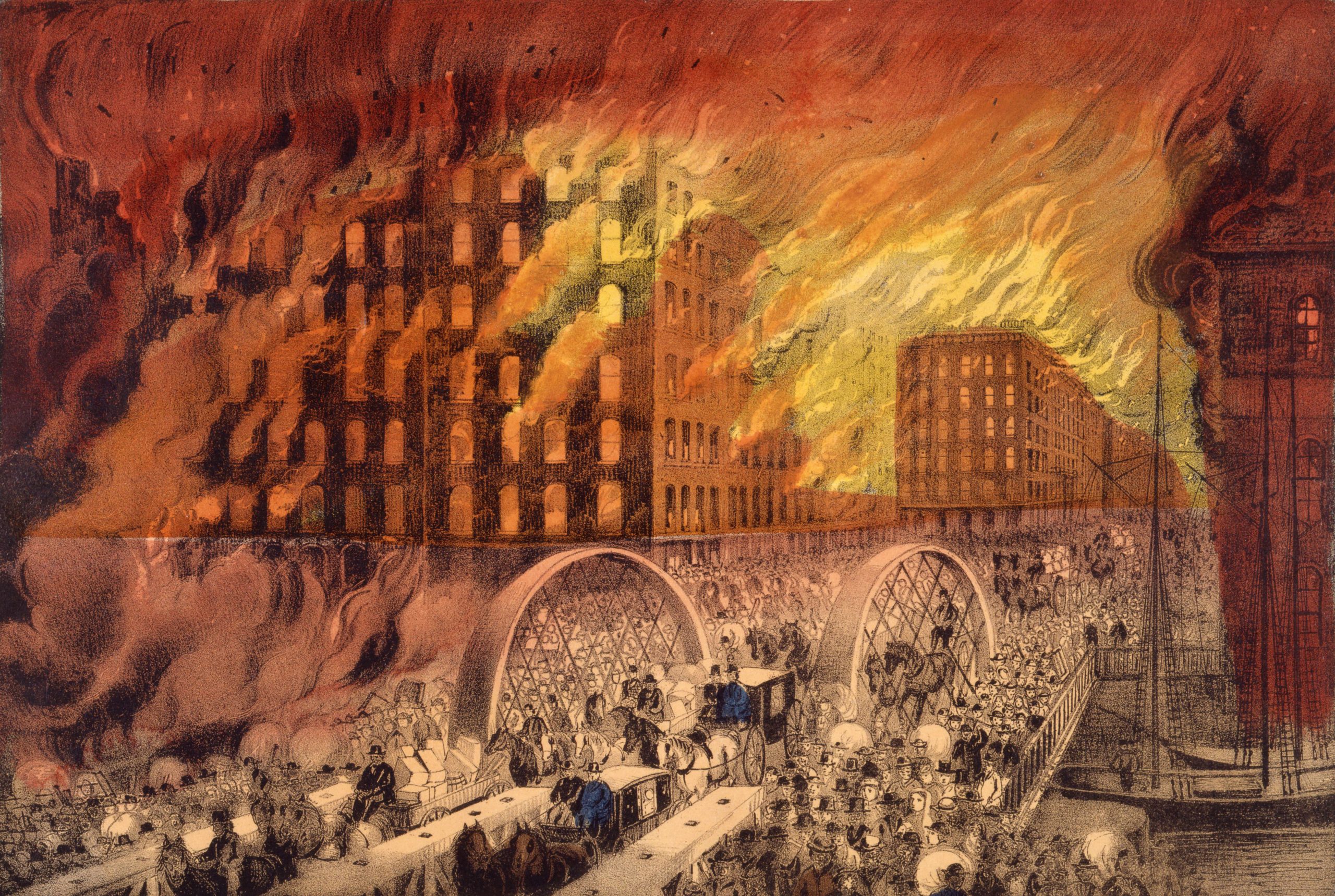

At about midnight, the South Branch of the Chicago River was ablaze because of the waste in it, and the fire reached downtown. It quickly swept through and destroyed everything in its path. As it neared the courthouse, Mayor Roswell B. Mason released the prisoners in the basement jail and telegraphed his counterparts in Milwaukee and Detroit for help.

It again jumped the river and spread to the North Side. By 2:30AM, the roof of the Water Works had collapsed, preventing water from getting to the hydrants. Residents, their arms filled with whatever they could save, fled north towards Lincoln Park and even into Lake Michigan for safety. Throughout Monday, the fire moved further up the North Side up to Fullerton Ave. Mason established a makeshift City Hall in a West Side church, established a relief committee, and signed orders against price gouging. The city finally received much-needed rain that night, which helped extinguish the fire, 32 hours after it began.

When added up, the damage was staggering. The fire spread four miles north and about a mile east, covering 28 miles of streets and 120 miles of sidewalks. Approximately 18,000 buildings were leveled—causing $192 million in property damage—and 100,000 people were left homeless. Somehow, only an estimated 200-300 people died in the blaze, with only 120 bodies recovered.

If there was one silver lining, it was that the winds blowing to the north spared the Union Stock Yards a few miles south of the fire’s origin, as well as the grain elevators and railroad infrastructure. The city’s predominant industries—meat processing and shipping—were virtually undisturbed and goods and aid could arrive and start the rebuilding process.

Also untouched, miraculously, was the O’Leary’s cottage. Neighbors told Michael Ahern of the Chicago Republican that the fire started when Catherine was milking one of her cows, Daisy, who kicked over a lantern. When questioned, Mrs. O’Leary swore she had gone to bed, and was never charged with a crime.

Regardless, she was still blamed for the disaster, in no small part because she was a poor, immigrant, Irish woman. Although she was likely between 35 and 45, Mrs. O’Leary was often depicted as a drunken old hag, and was even accused of deliberately starting the fire because she was Catholic and therefore more loyal to the Pope than America. The O’Learys eventually relocated to Back of the Yards. Catherine refused all interview requests and spent her remaining 24 years as a recluse, leaving the house only to go to mass and run errands.

In the public’s need for a scapegoat, nobody wondered why someone would be milking a cow at night.

On the 50th anniversary of the fire, Ahern admitted to fabricating the story and apologized to Mrs. O’Leary. But her story persisted, in song (“O’Leary’s Cow” and “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight”), film (In Old Chicago), and painting (by Norman Rockwell). She and Daisy were officially absolved by an act of the City Council…in 1997.

It remains unclear how the Great Chicago Fire started. Some historians believe that Daniel “Peg Leg” Sullivan, the first person to report the fire, started it while stealing milk and blamed the cow. Others say that the McLaughlin’s, who were renting the front part of the O’Leary’s cottage, were having a party to welcome a relative from Ireland, and a member went into the barn to get milk. Less detailed theories involve people a dice or card game or kids smoking in the barn. Still another theory points to a meteor shower that led to similar fires that night in Michigan and Peshtigo, Wisc.

The site of the O’Leary’s barn was eventually purchased by the city. Since 1961, it’s been the home the Chicago Fire Academy. Egon Weiner’s bronze sculpture “Pillar of Fire” is found in front as a memorial.

The Adventure starts when you say it does.

All eATLAS Adventures are designed and built by experienced eATLAS Whoa!Guides. They're always on. Always entertaining. And always ready to go.

Check out our Adventures!