How Chicago Shaped Abraham Lincoln

Published on October 6, 2023

eATLAS has a “Looking for Lincoln in Chicago” Adventure that takes you to seven places exploring Abraham Lincoln’s time in the Windy City. We also have a similar experience in Macomb, Ill., located 240 miles from Chicago.

By Dave Lifton (@daveeatschicago)

On its license plates, Illinois proudly boasts of being the Land of Lincoln. Although Abraham Lincoln is primarily associated with his adopted hometown of Springfield, it’s possible he could not have achieved much without Chicago.

Lincoln’s first visit to Chicago was in 1847, during his only term in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was one-third of a delegation representing Sangamon County at the River and Harbor Convention. The three-day event was designed to shore up support for increased funding for waterways, primarily in the Great Lakes region. Lincoln only spoke briefly, but he made an impression on the Whig Party elite, albeit for the wrong reasons.

“His dress and personal appearance on that occasion could not well be forgotten,” future Secretary of State Elihu B. Washburne recalled. “No one who saw him can forget his personal appearance at that time. Tall, angular and awkward, he had on a short-waisted, thin swallow-tail coat, a short vest of the same material, thin pantaloons, scarcely coming to his ankles, a straw hat and a pair of brogans with woolen socks.”

Despite being only 38, Lincoln was given the nickname “Old Abe” by the group who saw him.

Lincoln’s last trip to Chicago as a congressman was in 1848, where he gave a well-received two-hour speech in favor of Whig presidential candidate Gen. Zachary Taylor. A year later, Lincoln left office and resumed his law practice in Springfield, although he returned to Chicago to deliver a eulogy for Taylor, who died only 16 months into his term.

Meanwhile, the Whigs were splitting on the issue of slavery. In 1854, a Cleveland newspaper publisher named Joseph Medill helped found the Republican Party as an anti-slavery response to the Whigs. A year later, Medill and Dr. Charles Ray bought the Chicago Press and Tribune to give greater voice to the fledgling party. This put them in the orbit of Lincoln, who frequently came to Chicago to speak before the U.S. District Court.

As Lincoln made a greater name for himself in Illinois politics and the Republican Party, Medill became Lincoln’s biggest booster. The Tribune published his speeches, wrote favorable editorials, and defended him from attacks. Medill coached him in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, telling him to attack Douglas on the slavery issue. Lincoln lost the race, but Douglas’ answers in the debate hurt his standing among Democrats in the North.

Undaunted, the Tribune continued hyping Lincoln, with Medill and Ray eventually convincing him to run for president. Although Lincoln was known in Illinois Republican circles, he was considered unelectable because he had no national profile and was unsuccessful in two attempts at the Senate. He was so off the radar that Medill was able to convince the party to hold its convention in Chicago because the city would be a neutral site.

That May, the 1860 Republican National Convention was held in the Wigwam, a hall built at Lake St. and Market St. (now Wacker Dr.) specifically for the event. Of the 13 men, Lincoln was among the longest of the long shots, a vice presidential choice at best given that he was from Illinois, a swing state. New York Sen. William Seward and former Ohio Gov. Salmon Chase were the frontrunners. But some were worried that Seward’s pro-immigration and pro-Catholic stance would split the nascent party, and Chase’s status as a former Democrat caused the former Whigs to be wary. Of the others, their previous policies alienated assorted factions of the coalition. After four ballots, Lincoln emerged victorious and won the general election that November.

After Lincoln’s assassination on April 14th, 1865, a three-week funeral procession traced, in reverse order, his journey from Springfield to Washington prior to his first inauguration. Chicago became the penultimate stop. The train arrived on May 1st via the Illinois Central Railroad tracks 300 feet out on Lake Michigan. His casket was carried under a 40-foot arch, designed by W.W. Boyington, at Michigan Ave. and 12th St. (now Roosevelt Rood). The procession made its way up Michigan, turned west at Lake St., then went back south at Clark St. to the Cook County Courthouse. His body lay in state for 27 hours as 7,000 people an hour paid their respects. At 9:30 PM on May 2nd, the train left Chicago en route to his final resting place in Springfield.

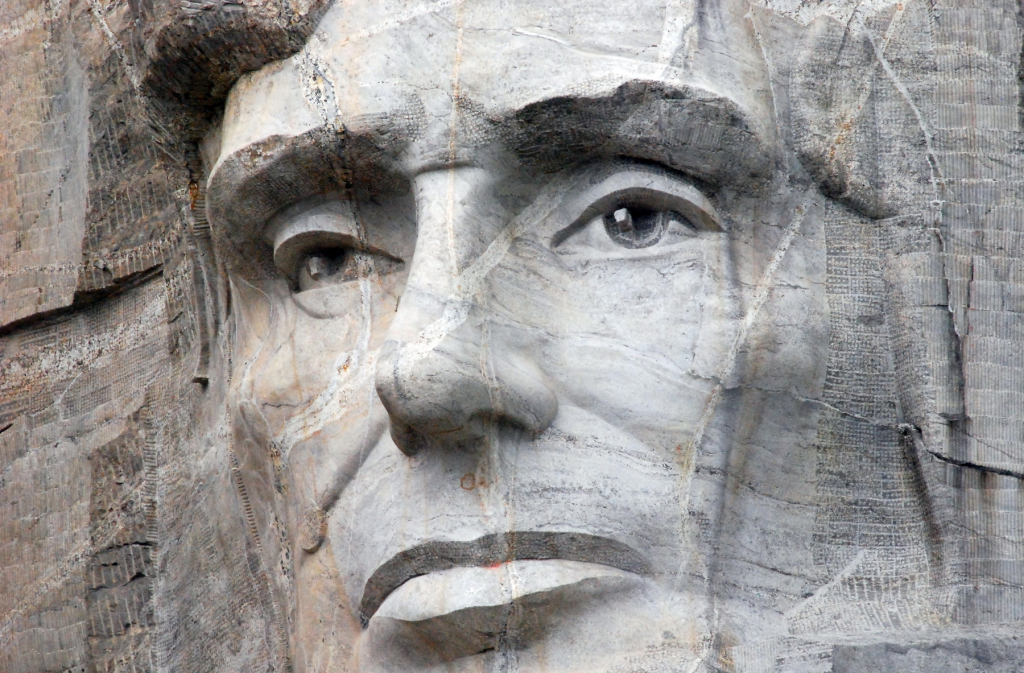

The Windy City’s love of the 16th president can be seen today through Lincoln Park (both the park and the neighborhood), Lincoln Square, and the suburbs of Lincolnwood and Lincolnshire. Statues of Lincoln are found in Lincoln Park, Grant Park, and Edgewater’s Senn Park, and River West even has a book store dedicated to scholarly works about Lincoln and the Civil War.

The Adventure starts when you say it does.

All eATLAS Adventures are designed and built by experienced eATLAS Whoa!Guides. They're always on. Always entertaining. And always ready to go.

Check out our Adventures!