Happy Mexican Independence Day!

Published on September 14, 2023

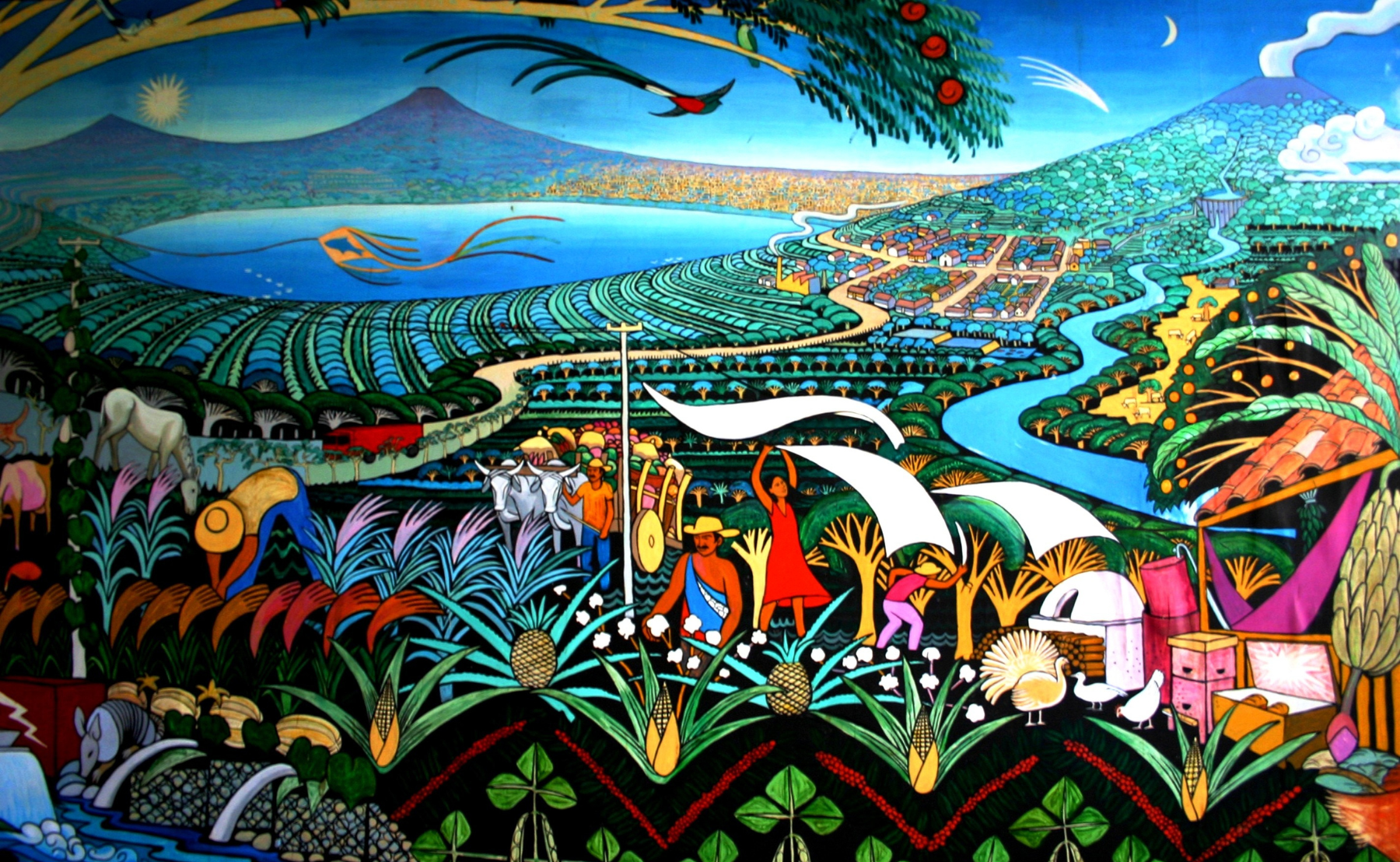

In celebration of Mexican Independence Day, eATLAS is exploring the history of Chicago’s Mexican community. We have two tours of Pilsen—Frida & Friends: Food & Art in Pilsen is a walking tour of the neighborhood, while Revolutionary Ride (available in English and Spanish) explores the public art in Pilsen and Humboldt Park by bicycle.

By Dave Lifton (@daveeatschicago)

These days Chicago has a thriving, vibrant Mexican community. But unlike many of the other immigrant groups that have settled in the Windy City, the history of Mexicans in Chicago is comparatively recent, and they’ve had a more difficult transition to assimilation.

In the mid-1910s, a combination of political turmoil due to the Mexican Revolution and the need for industrial manpower in World War I led to the first wave of Mexican migration to Chicago. They settled near where they worked, either in South Chicago (steel mills), Back of the Yards (meatpacking), or the Near West Side (railroads). By 1930, the city had 20,000 Mexicans, less than 1 percent of the total population of 3.3 million.

However, during the Great Depression, Mexicans took the brunt of the blame for taking what little work was to be found. This led to repatriation, both enforced and voluntary, and the city’s Mexican population was cut in half by the end of the 1930s. American involvement in World War II again brought the need for more labor, and a series of pacts beginning in 1942 resulted in increased Mexican migration to the U.S. But as the population swelled over the next decade, policies that targeted Chicago’s Mexican community were enacted at both the local and federal level.

On Sept. 16, 1954, Mexican Independence Day, Immigration and Naturalization Service agents began rounding up undocumented Mexicans in Chicago under an operation that used an anti-Mexican slur as its name. A Chicago Tribune article reported that the city sent three planes loaded with Mexican laborers back across the border every week.

Two years later, the Chicago Land Clearance Commission began a plan to seize and raze a Mexican section of the Near West Side—which had been used for generations as a hub for immigrants thanks to Jane Addams’ Hull-House—to build the University of Illinois – Chicago. Then, Back of the Yards was rezoned to end residential construction to stop more Mexicans from moving in.

This all coincided with the post-war movement to the growing suburbs that became known as “white flight,” which resulted in a glut of affordable housing on the working-class South and West Sides. Those displaced by the construction of UIC moved south to Pilsen, while the Mexican community in Back of the Yards stayed put and extended westward as Chicago’s Mexicans population continue to grow.

In an effort to distinguish itself from North Lawndale, which was rapidly becoming an African American neighborhood, the still-White South Lawndale was rebranded as Little Village in 1964. The new name took hold, but the exodus continued, with Mexicans moving in.

Over the next 20 years, the West and Southwest Sides became predominantly Mexican, with Pilsen and Little Village serving as the cultural anchors. Little Village (“La Villita”) became the “Mexico of the Midwest,” with a two-mile stretch of W. 26th St. becoming its main commercial corridor that is the second highest-grossing street in the city, behind only Michigan Ave.

Pilsen’s commercial streets are similarly filled with shops and restaurants, but it added a political streak, with murals of Latinx pride and self-determination popping up. In 1970, Casa Aztlán opened as a community center that offered everything from art, music, and dance classes to social services and legal advice. Shortly thereafter, local activists fought a plan to extend downtown Chicago through Pilsen in the name of urban renewal. The success revealed how the community had grown since the displacement 15 years earlier, but also that it needed more power to make sure that it wouldn’t happen again. Pilsen has gentrified over the past 20 years, but it remains majority Latinx, and the City Council has taken steps to slow new residential developments in the neighborhood.

In 1990, an arch was placed above the 3100 block of W. 26th St. Designed by Adrián Lozano, who took inspiration from arches that can be found on missions and haciendas across Mexico, it bears the inscription, “Bienvenidos a Little Village”—“Welcome to Little Village.” The bronze clock atop the arch was a gift from Carlos Salinas de Gortari, then the President of Mexico, during a 1991 visit to Chicago. It was made by Relojes Centenario, the oldest clockmaker in Mexico. The arch was named a Chicago Landmark in January 2022 by unanimous approval from the Commission on Chicago Landmarks.

Today, there are 670,000 people of Mexican descent in Chicago, almost 25 percent of the city’s population, and more than any other city in the U.S. except Los Angeles. Their influence and culture can be felt not just on the West Side, but throughout the city. That even extends to the Magnificent Mile, where the Colores Mexicanos gift shop opened in 2021, with a 10-foot statue of Catrina, a traditional symbol of the Day of the Dead, installed in a planter outside its door a year later.

The Adventure starts when you say it does.

All eATLAS Adventures are designed and built by experienced eATLAS Whoa!Guides. They're always on. Always entertaining. And always ready to go.

Check out our Adventures!