Iconic Chicago: Marshall Field & Co. – from rags to riches

Published on January 26, 2023

Our monthly series Iconic Chicago looks at some of the most famous locations in our city. We’ll explore the history of these places and why they have earned the love of residents and tourists alike. The latest installment of Iconic Chicago explores the history of Marshall Field, both the landmark State Street store and the man who built it.

The story of Marshall Field & Co. is distinctly American. It’s a rags-to-riches tale of someone who headed west from the East Coast and made his fortune through dreaming big, overcoming adversity, and innovation.

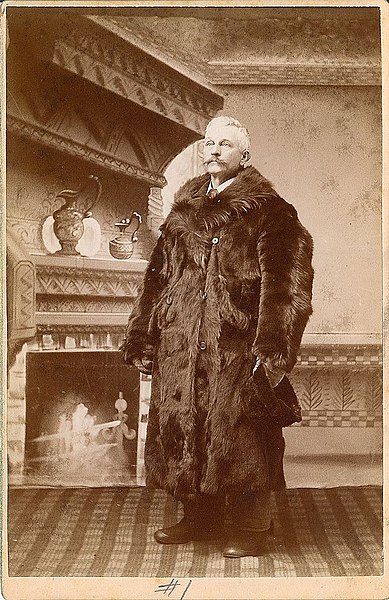

Born in 1834, Marshall Field spent the first 17 years of his life on a farm outside Conway, Mass. He then moved 40 miles west to Pittsfield to work as a clerk in Henry Davis’ store with his older brother, Joseph. Field’s salary was $10 a week. In 1856, Marshall rejected Davis’ offer of partnership and followed Joseph to Chicago in search of greater opportunities in the rapidly growing new city.

Marshall soon found work as a salesman for Cooley, Wadsworth & Co.’s, the city’s leading wholesaler. There, his attention to detail and work ethic—he slept in the store for the first year—impressed his bosses. By 1862 a series of shakeups at the top led to him becoming a partner. The company reorganized with him and John V. Farwell in charge. However, personality differences between Field and Farwell meant that the relationship, however profitable, was never meant to last

Enter Potter Palmer

By the time Marshall Field arrived in Chicago, another East Coast transplant, Potter Palmer, had been running his own successful store on Lake St. But the daily grind affected his health, and in 1865 his doctor advised him to get out of the retail business. Palmer then recruited Field and his junior partner, an accountant named Levi Leiter, away from Farwell, and their new store was named Field, Palmer, Leiter & Co.

Within two years, Field and Leiter were in a financial position to buy out Palmer, as had been the plan. Palmer devoted his attention to real estate, buying up much of the available land on State St., including the site where he would soon build the Palmer House Hotel and the northeast corner of State and Washington, the latter of which he leased to Field and Leiter in 1868.

The new store would become known as the “Marble Palace,” but not for long. It was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Thanks to heroic efforts by employees, much of the merchandise and the store’s records were saved and brought to Leiter’s house before the blaze could consume the building. The store’s insurance policy covered $2.5 million of the $3.5 million it lost, and Field, Leiter & Co. was able to reopen a few weeks later in a barn at State and 20th St.

They returned to State and Washington in 1873 to a building owned by the Singer sewing machine company, yet another fire claimed it four years later. Field & Leiter then operated in the Interstate Industrial Exposition Building, an underused convention center in Grant Park that sat on the site of what is now the Art Institute of Chicago. A third store at State and Washington, again owned by Singer, opened in 1879. But the relationship between Field and Leiter grew strained in the aftermath of the second fire. Two years later, Field bought out his longtime partner, and the store was renamed Marshall Field & Co.

Creating an Icon

Now in complete control of his business, Field set out to turn his store into the institution it would become. To assist him, he looked to a pair of men who started as stockboys and worked their way up through the ranks. John G. Shedd was placed in charge of the wholesaling division, which constituted nearly 80 percent of the company’s revenue at the time. In 1887, Field opened a seven-story warehouse on the block bordered by Wells, Adams, Franklin and Quincy Sts. The Henry Hobson Richardson-designed building took two years to construct and cost $888,807.

That same year, Field promoted Harry Selfridge to run the retail store. Selfridge implemented many concepts that followed Field’s oft-quoted credo, “Give the lady what she wants.” Selfridge not only gave the ladies what they wanted, he gave them what they didn’t know they needed. He instituted an unprecedented refund policy, a bridal registry, bargain basement to clear out older merchandise, display tables and counters, a personal shopping service, and annual sales. He hired Arthur Fraser to design the store’s elaborate window displays.

It wasn’t too long beforelong that Fraser’s windows were being obscured by people sticking notes into the frames to arrange meetings at the Singer Building. In order to keep the windows clear, Field had a clock placed above the corner in 1897 so that it could be used as a meeting spot.

Under Selfridge’s command, Marshall Field’s became the template for the American department store. With its highbrow interiors and attentive sales clerks, middle-class patrons were treated as if they were wealthy, while more well-heeled customers could find high-quality goods at reasonable prices.

Selfridge’s most iconic contribution might be the installation of a tearoom, unheard of in a department store. The oft-told story of it starting with Mrs. Hering, a saleslady in the hat department, sharing her chicken pot pie with a customer may or may not be entirely accurate. However, it’s known that a Sarah Haring was hired to run the tearoom during Selfridge’s tenure and left around 1910.

Building the Block

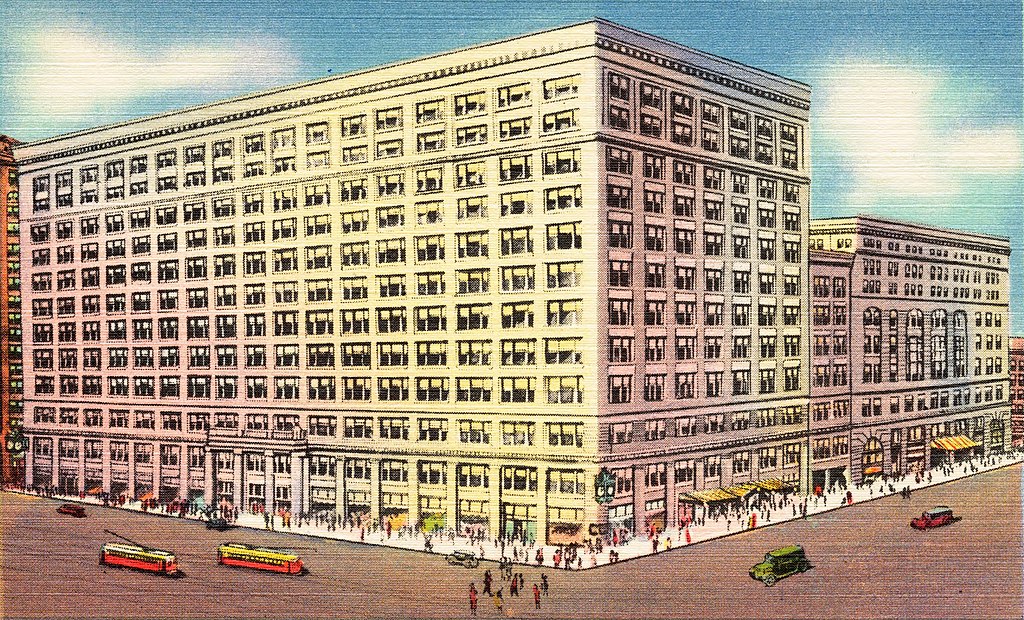

By 1891, Field had started talking openly about expanding his empire to encompass the entire block on which his store stood. He’d been acquiring parcels over the previous three years, including the Central Music Hall on the corner of State and Randolph and several others on Washington. Within a year, he owned the remainder of the Washington side, and the Daniel Burnham-designed nine-story “Annex” opened at the corner of Wabash and Washington in August 1893, adding more than 100,000 square feet of floor space to Marshall Field’s. Two stories were added to the Singer Building four years later.

Central Music Hall and the two State St. lots directly south were the first to meet the wrecking ball. In their place was another Burnham creation, a 12-story, white granite structure with four 50-foot columns in the center of the block, a clock that mirrored the one on the opposite corner, and an atrium with a skylight. The addition opened on Sept. 29, 1902 with an estimated 150,000 customers passing through its entrance.

Selfridge left in 1904 after Field refused to make him an equal partner. He bought the rival Schlesinger & Mayer store on State and Madison a block south of Marshall Field’s, but soon sold it to Carson Pirie Scott. He moved to London and opened his own Oxford Street store, Selfridges, in 1909. It remains in business.

On New Year’s Day 1906, Field was playing a round of golf in New York and contracted pneumonia. He died two weeks later at the age of 71. On the day of the funeral, businesses throughout Chicago were closed and the Chicago Board of Trade suspended trading.

By the time of Field’s death, he had approved the next set of expansion plans. That year, more lots along Wabash north of the Annex were incorporated into the store, and the Singer Building came down. On Sept. 30, 1907, the new store opened and was unlike any that had ever been seen. A second atrium was topped by a shimmering 6,000-square-foot, 1.6 million-piece glass dome designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, his largest mosaic using the Favrile process that he invented. Directly above it on the seventh floor was the South Tea Room, in which the store’s first Christmas tree was placed that year. The restaurant was renamed the Walnut Room in 1934.

The company was able to secure a 99-year lease for the Trude Building on the corner of Randolph and Wabash in 1912. It was folded into Marshall Field’s two years later, giving the company the entire block, as Field had envisioned 25 years earlier. Its 2 million square feet made it the second largest department store in the U.S., after Macy’s flagship in New York’s Herald Square. That same year, a men’s store opened in the first seven stories of a new 20-story building at 25 E. Washington. A tunnel connected it to the main store across the street.

Marshall Field’s Expands

Shedd retired in 1923 and was replaced by James Simpson, who started as a clerk in the cashier’s office and became a vice president upon Field’s death. Simpson’s brief tenure was one of growth. That year, they bought the A.M. Rothschild store on State and Jackson Sts. and converted it into the Davis Store, a discount shop. In 1928, the company purchased Seattle’s Frederick & Nelson, bringing with them the Frango mint chocolates that were made for the next 70 years on the 13th floor of the State Street store. Due to increased demand, production was outsourced to a Pennsylvania factory in 1999. The Frango brand has since been purchased by another classic Chicago confectioner, Garrett Popcorn.

Marshall Field’s also opened its first branches, with stores in Lake Forest, Evanston, and Oak Park arriving in 1928-9. While the retail side was thriving, the wholesale business was in decline. In the hopes of turning it around, Simpson decided to upgrade the aging Wells St. warehouse with the Merchandise Mart, an Art Deco masterpiece on the riverfront that, at 4 million square feet, was the largest building in the world when it opened in 1930 at a cost of $15 million. Unfortunately, the Great Depression had taken hold by this time and the wholesale business plummeted further. Simpson resigned two years later and the wholesale side of Marshall Field & Co. was disbanded by the mid-1930s.

Marshall Field’s weathered the Great Depression, although the Davis Store only lasted until 1936. Thanks to the 1945 sale of the Merchandise Mart to Joseph P. Kennedy, the company was able to open more stores as the suburbs began to grow in the years following World War II. For Chicagoans, the flagship location became synonymous with Christmas, thanks to the Walnut Room, with its giant tree and chicken pot pies, and the themed window displays featuring Uncle Mistletoe and Aunt Holly, a couple created by the store to compete with Montgomery Ward’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

End of an Era

As the store approached its 100th anniversary, Marshall Field’s descendants had long sold off their stake in the company, and no members of the Field family were directly involved with the running of the business. Expansion continued, with more stores opening in the suburbs and the acquisition of other retailers from as far away as the Pacific Northwest and the Southeast. The store at 111 N. State St. was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

In 1982, Marshall Field & Co. fought off a hostile takeover from investor Carl Icahn by selling itself to BATUS, Inc., the American arm of British American Tobacco that had been acquiring other retailers, including Saks Fifth Avenue and Gimbel’s over the previous decade. The price was $310 million. BATUS closed several underperforming stores and, by 1990, had divested itself of all its retail assets, with Marshall Field’s going to Minneapolis’ Dayton-Hudson, the parent company of Target. That lasted until 2004, with the May Co. purchasing Marshall Field’s.

But a year later, May was bought by Federated, which also owned Macy’s, and announced that all 62 Marshall Field stores would be rebranded as Macy’s. The change took effect in September 2006, despite protests from longtime patrons. For all the fear about what the loss of the Marshall Field’s brand would mean, the State St. store has retained some of its most iconic features—the Walnut Room, Tiffany dome, Frango.

Then, in 2018, Macy’s announced that it was selling the top half of 111 N. State St., most of which was taken up by the store’s offices, to Toronto’s Brookfield Asset Management for $30 million. As part of the conversion of the upper floors to new office space, one escalator bank in the central atrium was removed and a new lobby built at the entrance at 24 E. Washington St.

Many will argue that a piece of Chicago died when Marshall Field’s became Macy’s. But it could also be said that Marshall Field’s wasn’t the same after the post-war expansion, or when Field passed away, or even when Harry Selfridge departed. The history of Marshall Field and the store he built proves that the only constant is change.

One thought on "Iconic Chicago: Marshall Field & Co. – from rags to riches"

Leave a Reply

The Adventure starts when you say it does.

All eATLAS Adventures are designed and built by experienced eATLAS Whoa!Guides. They're always on. Always entertaining. And always ready to go.

Check out our Adventures!

Excellent article! Learned things I never new about this icon. I grew up with Marshall Fields and like so many of us “purists” still call the flagship location, “Fields.” Thankfully, they preserved the Frangos!